This Web page has been archived on the Web.

This Web page has been archived on the Web.

Archived Content

Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the Contact Us page.

Recovery Strategy for the Spotted Gar (Lepisosteus oculatus) in Canada

2.7 Critical Habitat

2.7.1 Identification of the Spotted Gar’s critical habitat

The identification of critical habitat for Threatened and Endangered species (on Schedule 1) is a requirement of the SARA. Once identified, SARA includes provisions to prevent the destruction of critical habitat. Critical habitat is defined under section 2(1) of SARA as:

“…the habitat necessary for the survival or recovery of a listed wildlife species and that is identified as the species’ critical habitat in the recovery strategy or in an action plan for the species”. [s. 2(1)]

SARA defines habitat for aquatic species at risk as:

“… spawning grounds and nursery, rearing, food supply, migration and any other areas on which aquatic species depend directly or indirectly in order to carry out their life processes, or areas where aquatic species formerly occurred and have the potential to be reintroduced.” [s. 2(1)]

For the Spotted Gar, critical habitat has been identified to the extent possible, using the best available information. The critical habitat identified in this recovery strategy describes the geospatial areas that contain the habitat necessary for the survival or recovery of the species. The current areas identified may be insufficient to achieve the population and distribution objectives for the species. As such, a schedule of studies has been included to further refine the description of critical habitat (in terms of its biophysical functions/features/attributes as well as its spatial extent) to support its protection.

2.7.2 Information and methods used to identify critical habitat

Using the best available information, critical habitat has been identified using a ‘bounding box’ approach for the three coastal wetlands where the species presently occurs. This approach requires the use of essential functions, features and attributes for each life-stage of the Spotted Gar to identify patches of critical habitat within the ‘bounding box’ which is defined by occupancy data for the species. Life stage habitat information was summarized in chart form using available data and studies referred to in Section 1.4.1 (Habitat and biological needs). The bounding box approach was the most appropriate, given the limited information available for the species and the lack of detailed habitat mapping for these areas. Where habitat information was available (e.g., Ecological Land Classification [ELC], bathymetry data), it was used to inform identification of critical habitat. Specific methods and data used to identify critical habitat (such as the use of ELC) is summarized below (for more detailed information refer to Appendix 2).

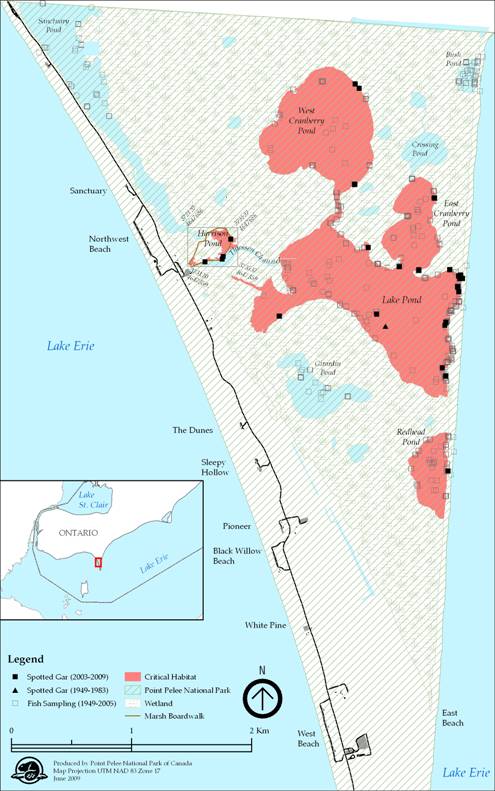

Point Pelee National Park: Sampling data for Spotted Gar for the ponds within the park were taken from the studies of Surette (2006), Razavi (2006), A.-M. Cappelli (unpublished data, 2009) and B. Glass (unpublished data, 2009) as well as photographic documentation in 2007 (S. Staton). Pond names were taken from the National Topographic System (NTS) series of maps.

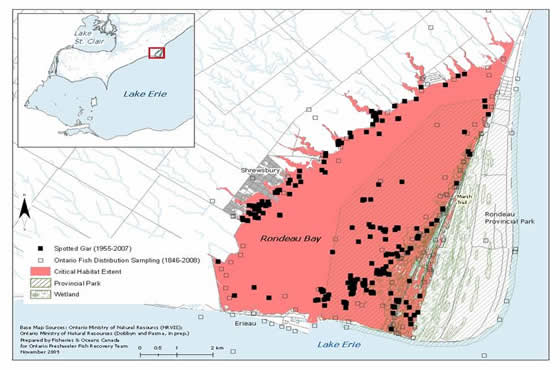

Rondeau Bay: Sampling data for Spotted Gar was taken from the DFO database for the period from 1955 to 2004 as well as the extensive capture (total of 210 specimens) and tracking data from 2007 (B. Glass, unpublished data). Within Rondeau Provincial Park, critical habitat was refined using available ELC data for the park. ELC assesses the distribution and groupings of plant species and attempts to understand them according to ecosystem patterns and processes. It also helps to establish patterns among vegetation, soils, geology, landform and climate, at different scales. Using the factors relating to geology, soils, physiography and vegetation, ELC can be used to map vegetation communities at varying organizational scales (Lee et al. 1998, Lee et al. 2001). Spotted Gar capture locations within the park were compared with the park ELC data (Dobbyn and Pasma, in prep.) to determine the wetland vegetation types used by the species. All areas containing these ELC types were initially included as critical habitat; however, aquatic habitats that were isolated from the waters of the bay were excluded as these areas are inaccessible to Spotted Gar.

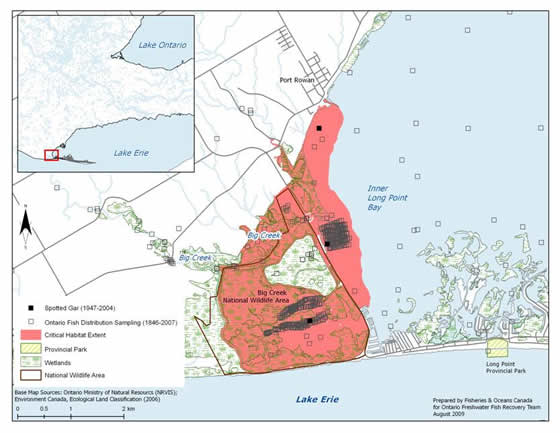

Long Point Bay/Big Creek NWA: Limited data are available for the Spotted Gar population in Long Point Bay; there are currently 11 records for Spotted Gar in Inner Long Point Bay, the most recent of which is from 2010 (B. Glass, unpublished data). Capture data for Big Creek NWA (connected to Long Point Bay) were taken from one location (L. Bouvier, DFO, pers. comm. 2008).

Critical habitat was identified in these areas using ELC, as the wetland (including marsh, meadow marsh, shallow marsh, common reed, floating-leaved and mixed shallow aquatic, and thicket swamp ELC community classes) and aquatic (less than 2 m depths including open aquatic, submerged shallow aquatic, and open-submerged-floating-leaved, mixed ELC community classes) within Big Creek NWA, Inner Long Point Bay and the mouth of Big Creek.

Population Viability:

Comparisons of the area of critical habitat identified for each population were made with estimates of the spatial requirements for a minimum sustainable population size. The minimum area for population viability (MAPV) for each life-stage of the Spotted Gar was estimated for populations in Canada (refer to Section 2.7.4). The MAPV is defined as the amount of exclusive and suitable habitat required for a demographically sustainable recovery target based on the concept of a minimum viable population size (MVP) (Vélez-Espino et al. 2008). Therefore, the MAPV is a quantitative metric of critical habitat that can assist with the recovery and management of species at risk (Vélez-Espino et al. 2008). The estimated MVP for adult Spotted Gar is approximately 14 000 individuals and the associated MAPV is estimated to be 35 km², given a 15% chance of a catastrophic event occurring per generation and an extinction threshold of 20 individuals (i.e., the adult population size below which the population is considered extinct). (For more information on the MVP and MAPV values for Spotted Gar refer to Young and Koops [2010].)

MAPV values are somewhat precautionary in that they represent the sum of habitat needs calculated for each life-history stage of the Spotted Gar; these figures do not take into account the potential for overlap in the habitat of the various life-history stages and may overestimate the area required to support an MVP. However, since many of these populations occur in areas of degraded habitat (MAPV assumes habitat quality is optimal), areas larger than the MAPV may be required to support an MVP. In addition, for some populations, it is likely that only a portion of the habitat within that identified as the critical habitat extent would meet the functional requirements of the species’ various life-stages.

2.7.3 Identification of critical habitat: biophysical functions, features and their attributes

There is limited information on the habitat needs for the various life stages of the Spotted Gar. Table 8 summarizes available knowledge on the essential functions, features and attributes for each life-stage (refer to section 1.4.1 Habitat and biological needs for full references). Areas identified as critical habitat must support one or more of these habitat functions.

| Life Stage | Function |

Feature(s) |

Attribute(s) |

Adult and early life stage from Spawn to embryonic (yolk sac or < 17mm TL) |

Spawning (May to June)

|

Coastal wetlands and connected quiet backwater areas along the north shore of Lake Erie: including interconnected flooded riparian areas and contributing channels. |

|

Larvae (Young of Year > 17mm TL) |

Nursery |

Coastal wetlands and quiet backwater areas along the north shore of Lake Erie: including interconnected flooded riparian areas and contributing channels. |

|

Juvenile [age 1 until sexual maturity (2-3 years males; 3-4 years females)] |

Feeding |

Coastal wetlands and connected quiet backwater areas along the north shore of Lake Erie: including interconnected flooded riparian areas and contributing channels.. |

|

Adult [from onset of sexual maturity (2-3 yrs for males; 3-4 years for females) and older] |

Feeding |

Coastal wetlands and connected quiet backwater areas along the north shore of Lake Erie: including interconnected flooded riparian areas and contributing channels. |

|

*where known or supported by existing data

Studies to further refine knowledge on the essential functions, features and attributes for various life-stages of the Spotted Gar are described in Section 2.7.5 (Schedule of studies to identify critical habitat).

2.7.4 Identification of critical habitat: geospatial

Using the best available information, critical habitat has been identified for Spotted Gar populations in the following areas:

1. Point Pelee National Park,

2. Long Point Bay/Big Creek NWA; and

3. Rondeau Bay.

Areas of critical habitat identified at these locations may overlap with critical habitat identified for other co-occurring species at risk (e.g., Lake Chubsucker in Point Pelee National Park, Rondeau Bay and Long Point Bay); however, the specific habitat requirements within these areas may vary by species.

The areas delineated on the following maps (Figures 6-8) represent the area within which critical habitat is found or extent of critical habitat for the above-mentioned populations that can be identified at this time. Using the ‘bounding box’ approach, critical habitat is not comprised of all areas within the identified boundaries, but only those areas where the specified biophysical features/attributes occur (refer to Table 8). Note that permanent anthropogenic structures that are present within the delineated areas (e.g., boardwalks, marinas, pumping stations) are specifically excluded; it is understood that maintenance or replacement of these features may be required at times. Brief explanations for the areas identified as critical habitat is provided for each of the 3 areas below.

Point Pelee National Park: The ponds within Point Pelee National Park, including Redhead Pond, Lake Pond, East Cranberry Pond, West Cranberry Pond and Harrison Pond, are identified as critical habitat. However, the watercraft passage between Harrison and Lake ponds known as Thiessen Channel (Figure 6) is excluded from this critical habitat description because it has been highly managed (modified and maintained) since at least 1922 to allow for watercraft passage from the western boundary of the marsh into Lake Pond and the other connecting ponds (Battin and Nelson 1978).

Figure 6. Critical habitat identified for Spotted Gar within Point Pelee National Park

Long Point Bay/Big Creek NWA: Big Creek NWA, the area around Inner Long Point Bay and the mouth of Big Creek (Figure 7) are included as critical habitat. The interior diked cell within Big Creek NWA where Spotted Gar have not been detected has been excluded (the diked cell is not accessible to Spotted Gar). The extent of critical habitat includes all contiguous waters and wetlands, excluding permanently dry areas, from the causeway west to and including all of Big Creek NWA, except habitat contained within the interior diked cell within the NWA, and including Big Creek proper and all contiguous wetlands to the north of Big Creek. Within Inner Long Point Bay, critical habitat extends north to the pier at Port Rowan and south, down to, but not including, the dredged channels of the marina complex (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Critical habitat identified in Long Point Bay/Big Creek NWA for the Spotted Gar

Rondeau Bay: Critical habitat for Spotted Gar is currently identified as the waters and wetland areas (including seasonally flooded wetlands) of the entire bay (Figure 8). This includes the mouths of tributaries flowing into the bay, upstream to the point where a defined stream channel is observed. Within Rondeau Provincial Park, aquatic habitats that were isolated from the waters of the bay were excluded as these areas are inaccessible to Spotted Gar. In particular, the areas identified as wetlands to the east of Marsh Trail actually contain large sections of upland terrestrial habitats that isolate interior wetland pockets (i.e., sloughs) (S. Dobbyn, OMNR, pers. comm. 2009). Approximately half of the identified critical habitat extent lies within Rondeau Provincial Park.

Figure 8. Critical habitat identified for the Spotted Gar within Rondeau Bay

The identification of critical habitat within Point Pelee National Park, Long Point Bay/Big Creek NWA and Rondeau Bay ensures that currently occupied habitat supporting Spotted Gar is protected, until such time as critical habitat for the species is further refined according to the schedule of studies laid out in Section 2.7.5. The recovery team recommends to the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans that these areas are necessary to achieve the identified survival and recovery objectives. The schedule of studies outlines activities necessary to refine the current critical habitat descriptions at confirmed extant locations, but will also apply to new locations should new locations with established populations be confirmed (e.g., East Lake, Hamilton Harbour). Critical habitat descriptions will be refined as additional information becomes available to support the population and distribution objectives.

2.7.4.1 Population Viability

In Table 9, comparisons were made with the extent of critical habitat identified for each population relative to the estimated minimum area for population viability (MAPV). It should be noted that for some populations, it is likely that only a portion of the habitat within that identified as the critical habitat would meet the functional habitat requirements of the species’ various life-stages. In addition, since these populations occur in areas of degraded habitat (MAPV assumes habitat quality is optimal), areas larger than the MAPV may be required to support an MVP. Future studies may help quantify the amount and quality of available habitat within critical habitats for all populations; such information, along with the verification of the MAPV model, will allow greater certainty for the determination of population viability. As such, the results in Table 9 are preliminary and should be interpreted with caution.

* The MAPV estimation is based on modeling approaches described above.

2.7.5 Schedule of studies to identify/refine critical habitat

This recovery strategy includes an identification of critical habitat to the extent possible, based on the best available information. Further studies are required to refine critical habitat identified for the Spotted Gar to support the population and distribution objectives for the species. The activities listed in Table 10 are not exhaustive and it is likely that the process of investigating these actions may identify additional knowledge gaps that will need to be addressed.

Activities identified in this schedule of studies will be carried out through collaboration between DFO, PCA, EC-CWS, the EERT, First Nations and other relevant groups and land managers. Note that many of the individual recovery approaches will address some of the information requirements listed above.

2.7.6 Examples of activities likely to result in destruction of critical habitat

The definition of destruction is interpreted in the following manner:

“Destruction of critical habitat would result if any part of the critical habitat were degraded, either permanently or temporarily, such that it would not serve its function when needed by the species. Destruction may result from single or multiple activities at one point in time or from cumulative effects of one or more activities over time.”

Under SARA, critical habitat must be legally protected from destruction once it is identified. This will be accomplished through a s.58 Order, which will prohibit the destruction of the identified critical habitat.

The Minister of Fisheries and Oceans invites all interested Canadians to submit comments on the potential use of a s.58 Order to protect the critical habitat of the Spotted Gar as soon as possible. Please note that, pursuant to s.58, any such Order must be operational within 180 days of the posting of the final version of the Recovery Strategy, or Action Plan, that identifies critical habitat.

Activities that increase siltation/turbidity levels and/or result in the removal of excessive amounts of native aquatic vegetation can negatively impact Spotted Gar habitat. However, in areas where nutrient loading has resulted in the extreme overgrowth of aquatic vegetation, small-scale vegetation removal may benefit the species. In these situations, dependent on site-specific reviews, small-scale vegetation removal projects using approved chemical and/or physical means may be allowed. Appendix 3 provides additional guidance on vegetation removal.

Without appropriate mitigation, direct destruction of habitat may result from work or activities such as those identified in Table 11.

The activities described in this table are neither exhaustive nor exclusive and have been guided by the General Threats described in Section 1.5 of the recovery strategy for the species. The absence of a specific human activity does not preclude, or fetter the department’s ability to regulate it pursuant to SARA. Furthermore, the inclusion of an activity does not result in its automatic prohibition since it is destruction of critical habitat (CH) that is prohibited. Since habitat use is often temporal in nature, every activity is assessed on a case-by-case basis and site-specific mitigation is applied where it is reliable and available. In every case, where information is available, thresholds and limits are associated with attributes to better inform management and regulatory decision-making. However, in many cases the knowledge of a species and its CH may be lacking and in particular, information associated with a species or habitat tolerance threshold to disturbances from anthropogenic activities, is not available and must be acquired.

| Activity | Effect - pathway |

Function affected |

Feature affected |

Attribute affected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Habitat modifications:

|

Changes in bathymetry and shoreline morphology caused by dredging and near-shore grading and excavation can remove (or cover) preferred substrates, change water depths, change flow patterns potentially affecting turbidity, nutrient levels, water temperatures, and migration. |

Spawning |

Coastal wetlands and connected quiet backwater areas along the north shore of Lake Erie: including interconnected flooded riparian areas and contributing channels. |

|

Habitat modifications: |

Placing material or structures in water reduces habitat availability (e.g., the footprint of the infill or structure is lost). Placement of fill can cover preferred substrates, aquatic vegetation and underwater structure. |

All (same as above) |

All (same as above) |

All (same as above) |

Habitat modifications: Change in timing, duration and frequency of flow |

Water extraction can reduce the availability of wetland habitats. Draining wetlands can reduce the availability of habitat used various life stages of this species. Water depths can be reduced, affecting aquatic plant growth, underwater structure that would provide cover and water temperatures. Organic inputs from drained wetlands could be reduced potentially affecting the availability of prey. |

All (same as above) |

All (same as above) |

All (same as above) |

Habitat modifications: |

When livestock have unfettered access to waterbodies damage or loss of riparian and aquatic vegetation can occur. Resulting damage to shorelines, banks and watercourse bottoms can cause increased erosion and sedimentation, affecting turbidity and water temperatures. |

Spawning |

All (same as above) |

|

Aquatic and riparian vegetation removal: |

Removal of aquatic or riparian vegetation required by the species to spawn and for cover can negatively affect recruitment and predation success. Plant die-off following chemical treatments and the removal of plant material can also negatively impact water quality, affect turbidity and water temperatures. |

All (same as above) |

All (same as above) |

|

Turbidity and sediment loading: |

Improper sediment and erosion control or inadequate mitigation can cause increased turbidity levels, potentially reducing feeding success or prey availability, impacting the growth of aquatic vegetation and possibly excluding fish from habitat due to physiological impacts of sediment in the water (e.g., gill irritation). |

Spawning |

All (same as above) |

|

Nutrient loadings: |

Poor land management practices and improper nutrient management can result in overland runoff and nutrient loading of nearby waterbodies Elevated nutrient levels can cause increased aquatic plant growth changing water temperatures. The availability of prey species can also be affected if prey are sensitive to organic pollution. |

All (same as above) |

All (same as above) |

All (same as above) |

|

Deliberate introduction of exotic species |

Feeding by Common Carp can increase turbidity and uproot aquatic vegetation that Spotted Gar may use for cover. |

Spawning |

All (same as above) |

All (same as above) |

Barriers to movement: |

The installation of structures that restrict fish passage can limit the movement of individuals, fragmenting populations. Flow alterations sometimes associated with these structures can impact habitat availability further (see: Habitat modifications: change in timing, duration and frequency of flow). Barriers can alter water levels upstream and downstream affecting habitat availability. |

Spawning |

All (same as above) |

All (same as above) |

Certain habitat management activities are recognized as being beneficial to the long-term survival and/or recovery of the species and may be allowed when required. Such activities may include the removal or control of exotic aquatic/semi-aquatic vegetation; water level management (including dike maintenance); and habitat restoration activities (e.g., fire management). For example, in NWAs, water levels may be managed and some aquatic vegetation may be removed to maintain hemi-marsh conditions (i.e., 50/50 emergent/open water habitat). Other restoration activities that improve the quality and/or quantity of available wetland habitat for the Spotted Gar may also be considered.

2.8 Existing and recommended approaches to habitat protection

Habitat of the Spotted Gar receives general protection from works or undertakings under the habitat protection provisions of the federal Fisheries Act. The Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (CEAA) also considers the impacts of projects on all listed wildlife species and their critical habitat where it has been identified. During the CEAA review of a project, all adverse effects of the project on a listed species and its critical habitat must be identified. If the project is carried out, measures must be taken that are consistent with applicable recovery strategies or action plans to avoid or lessen those effects (mitigation measures) and to monitor those effects.

Critical habitat for the Spotted Gar located in both Point Pelee National Park and Big Creek NWA will be protected by the prohibition against destruction of critical habitat, pursuant to subsection 58(2) of the SARA, 90 days after the description of critical habitat, as identified in the recovery strategy, is published in the Canada Gazette. This prohibition provides additional protection to that already afforded and available under the Canada National Parks Act and Canada Wildlife Act, respectively, as well as the regulations associated with those statutes. Individuals of listed species at risk populations located on lands and in waters under the administration of the federal government also receive protection under SARA once the species is listed on Schedule 1 of SARA.

Provincially, protection is also afforded under the provincial Planning Act. Planning authorities are required to be “consistent with” the provincial Policy Statement under Section 3 of Ontario’s Planning Act, which prohibits development and site alteration in the habitat of regulated Endangered and Threatened species. Stream-side development in Ontario is managed through floodplain regulations enforced by local conservation authorities. Under the Public Lands Act, a permit may be required for work in the water and along the shore. The Spotted Gar is listed as a Threatened species under Ontario’s Endangered Species Act, 2007. Under the Act, the species itself is currently protected, and the habitat of the Spotted Gar will be protected under the general habitat protection provisions of the Act as of June 20, 2013, unless a species-specific habitat regulation is developed by the provincial government at an earlier date.

Existing populations of Spotted Gar in Lake Erie are found in Point Pelee National Park, Rondeau Provincial Park (which represents the eastern portion of the bay only), Long Point Bay (including the NWA), and Big Creek NWA, which affords the species some protection. Currently occupied habitat receives additional protection afforded to NWAs through the Canada Wildlife Act, and provincial parks through the Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act.

Currently, recommended high priority areas for stewardship include Rondeau Bay watersheds where land use impacts appear to be compromising habitat conditions within the bay.

2.9 Effects on other species

It is conceivable that increased populations of Spotted Gar could result in increased predation of other co-occurring fishes at risk (e.g., Grass Pickerel [Esox americanus vermiculatus], Lake Chubsucker, Pugnose Minnow [Opsopoeodus emiliae], Pugnose Shiner [Notropis anogenus] and Warmouth [Lepomis gulosus]). However, the proposed recovery activities will benefit the environment in general and are expected to have a net positive effect on other sympatric native species. While there is potential for conflicts with other species at risk (aquatic and aquatic-dependent) during recovery implementation, this possibility will be minimized through strong coordination among the various recovery teams and groups/government agencies that may be working on species at risk and habitat management within the coastal wetland areas of Lake Erie. In addition, most stewardship and habitat improvement activities will be implemented through the Essex-Erie recovery initiative, which provides for a high awareness of other recovery programs. DFO, Environment Canada, and PCA recognize that an ecosystem approach to habitat management is necessary to ensure habitat management decisions address the needs of all species at risk within overlapping critical habitat areas (e.g., Least Bittern [Ixobrychus exilis], Spotted Gar, Lake Chubsucker).

2.10 Recommended approach for recovery implementation

This single species document is one component of recovery implementation for co-occurring species at risk found in the same location. The Ontario Freshwater Fish Recovery Team recommends making effective use of resources and reducing costs by coordinating efforts with relevant groups, the EERT and its associated RIGs in the areas where this species exists. The three coastal wetlands of Lake Erie inhabited by Spotted Gar have been identified by the EERT as primary core areas for directing recovery efforts to benefit this species. The EERT and its RIGs include representation from park agencies responsible for the management of these wetland habitats. This overlap of individuals affiliated with these plans will help ensure that recovery actions for the Spotted Gar mesh with existing park management plans. Although Spotted Gar is included in the Sydenham River Recovery Strategy (Dextrase et al. 2003), the original records for this watershed have since been deemed questionable (COSEWIC 2005).

2.11 Statement on action plans

Action plans are documents that describe the activities designed to achieve the recovery goals and objectives identified in recovery strategies. Under SARA, an action plan provides the detailed recovery planning that supports the strategic direction set out in the recovery strategy for the species. The plan outlines what needs to be done to achieve the recovery goals and objectives identified in the recovery strategy, including the measures to be taken to address the threats and monitor the recovery of the species, as well as the measures to protect critical habitat. Action plans offer an opportunity to involve many interests in working together to find creative solutions to recovery challenges.

One or more action plans relating to this recovery strategy will be produced within five years of the final strategy being posted to the SARA registry.

- Date modified: